Updated Oct 20, 2018

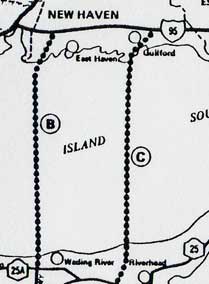

Two of five alternatives in the 1979 Long Island Sound Bridge Study would touch down in East Haven and Guilford. (see complete diagram)

Two of five alternatives in the 1979 Long Island Sound Bridge Study would touch down in East Haven and Guilford. (see complete diagram)

Long Island Sound, an estuary 110 miles long and up to 21 miles wide, separates Connecticut to the north and New York's Long Island to the south. Nearly 3 million people live in Nassau and Suffolk counties; adding the population of Kings and Queens counties brings the total to 8 million. On the other side of the Sound live over 3 million people in Connecticut and about 13 million overall in New England.

For decades, several options to bridge the Sound have been discussed, but none have been built.

Potential advantages to a cross-Sound bridge include:

Disadvantages include:

Several bridge or bridge-tunnel combinations have been proposed over the years to connect Long Island to the "mainland" in Connecticut and Rhode Island. In general, though this was not unanimous, New York favored a bridge and Connecticut opposed it; this was seen in state government as well as town officials and residents.

Though the bridge idea still enjoys popular support, especially in New York, there is no overwhelming mandate for it, and the significant costs are a large obstacle.

This page discusses several bridge proposals and refers to more detailed information (primarly, a tip of the hat to NYCRoads.com webmaster and historian Steve Anderson).

The idea for a bridge across the Sound dates back to the 1930s. Most comprehensive studies were done in the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1965, Bertram D. Tallamy Associates performed a study for the New York State Department of Public Works concerning a bridge from Long Island to New England, along with connectors to the existing highway system.

In all, 14 locations between Port Jefferson and Fishers Island were considered, all in the eastern half of Long Island. All but two (East Marion - Old Saybrook and Port Jefferson - Bridgeport) were eliminated as infeasible.

In early 1966, New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller began a concerted effort to build a bridge across the Sound. Connecticut was primarily cool on the idea, its opposition led by Sen. Abraham Ribicoff and US Rep. Stewart McKinney.

For three years, the sides fought over two planned bridges: East Marion - Old Saybrook and Port Jefferson - Bridgeport.

By 1973, Rockefeller was advocating a smaller proposal, running from Rye, N.Y. to Oyster Bay on Long Island. This might have extended I-287 across the Sound.

Creighton, Hamburg, Incorporated studied 8 bridge proposals for NYSDOT in 1971. (See summary at NYCRoads.com.) One of my favorite quotes from the summary:

Since the tollbooth region is a prime source of pollution, its location on the northern end of any bridge is strongly suggested.

"You weren't supposed to put that in the report!" I can hear NY officials saying :-)

The study concluded with a recommendation to build the Oyster Bay - Rye bridge (I-287), noting that the area's expressways were already in place to accommodate bridge traffic.

In 1979, New York Gov. Hugh Carey set up a tri-state advisory committee to study building a bridge across the Sound. The East Marion - Old Saybrook and Riverhead - Guilford bridges were studied. The committee's environmental impact task force concluded a bridge was "neither desirable nor necessary," and the final recommendation was for expanded ferry service.

Public sentiment against a bridge was particularly strong in eastern Long Island and in Connecticut.

Furthermore, the Long Island Sound Bridge Study concluded that no fixed crossing over the Sound could recover its costs from tolls. Bonds based on those revenues could only support 8% to 16% of construction costs, leaving deficits of $900 million or more.

Tunnels as well as bridges were studied in the 1960s and 1970s. The conclusions of the 1979 Long Island Sound Bridge Study: a tunnel would be a far worse idea than a bridge. Disadvantages of a tunnel:

Listed below are the proposals that were at some time considered feasible. Most included a connection to the two main highways on each side: I-95 (formerly the Connecticut Turnpike), and I-495 (the Long Island Expressway).

Some eastern proposals would have extended I-495 instead of building a spur.

Likely an interstate designation (I-495 or another x95) would have been extended over the bridge, giving Connecticut or Rhode Island another interstate highway.

Studied in 1971.

Studied in 1971.

A shorter crossing, entirely within New York State. Would have become an extension of I-287. This proposal had length, cost, and traffic demand advantages over the eastern bridges, but was defeated in 1973.

A similar proposal would connect to Glen Cove on Long Island.

See also:

This was studied earlier, but had been dropped by 1971.

This was studied in 1965 (Tallamy), and found economically infeasible. In 1968 (Wilbur Smith), the project was said to "open up untold market potential" in Bridgeport and the surrounding area, with similar benefits to Suffolk County.

This bridge and the East Marion - Old Saybrook bridge were advocated by New York officials from 1966 through 1969.

This would connect the Floyd Parkway to an extension of I-91. A 1971 study (Creighton, Hamburg) singled out this bridge as the only alternative of eight that would cause no significant air or noise pollution.

The Interstate 91 designation would be extended over the bridge to I-495 along an upgraded Floyd Parkway.

There were two alternatives for connecting roadways on the Connecticut side. Both would involve an overlap of I-91 and I-95 leading to the existing I-91 terminus.

See also:

Similar to the Shoreham - New Haven proposal, this would connect the Floyd Parkway to a possible extension of I-91. Studied in 1979.

See also:

This was proposed in 1971 or earlier. It was also studied in 1979 by a New York-run "tri-state advisory committee." In contrast to the other proposals that touch down in Connecticut, this one would lead to I-95 not near any freeways (e.g. CT 8, I-91, CT 9) leading to the state's interior.

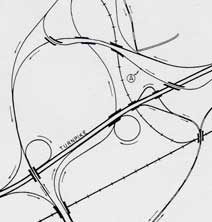

This sprawling, low-capacity interchange was proposed in a New York State-sponsored study in 1965 to connect the Old Saybrook crossing to I-95 and Route 9. This is quite possibly the worst interchange plan I have ever seen. For grins, see the complete diagram.

This sprawling, low-capacity interchange was proposed in a New York State-sponsored study in 1965 to connect the Old Saybrook crossing to I-95 and Route 9. This is quite possibly the worst interchange plan I have ever seen. For grins, see the complete diagram.

This was recommended to the New York State Department of Public Works as the best alternative for crossing the Sound, and a needed project. It was also one of two bridge proposals from 1966-1969 pushed by New York.

This bridge was further studied in 1979 at the behest of New York Gov. Hugh Carey's commission. Barbara Maynard, former first selectwoman of Old Saybrook, viewed the bridge as a threat: "We did not want to be the town at the end of that bridge."

A proposal c. 1966 by former Groton Mayor Clarence B. Sharp (CT 349 is named after him). An underwater tunnel would connect Orient Point to East Lyme near Rocky Neck. It might have used an upgraded SSR 449 connector to I-95 if built.

Any tunnel would be much more expensive to build and operate than a bridge, and this proposal foundered.

This was studied in 1965, and recommended against for cost reasons.

This is similar to the Tri-State Bridge proposal in 1963, without the spur to Groton.

See also:

New York officials and Long Island businessmen formed the Long Island Sound Tri-State Bridge Committee in 1963, proposing a three-part bridge:

This plan was later shelved in favor of the smaller-scale East Lyme tunnel proposal by former Groton Mayor Clarence B. Sharp (see above).

By January 1966 both proposals were on the back burner.

Extending a bridge over 20 or more miles of open water is not a trivial undertaking. However, several examples show how this can be done: